Taking a boat ride between islands in the Indian Sundarbans could be fun and enjoyable if you are there for tourism. It may not be very easy to be living in a very uncertain, harsh and difficult environment like this though. Mrs. Anwara Khatoon (name changed) says “It is very difficult surviving under these conditions – with my husband and elder son migrating to the city for a living, our small piece of land completely submerged under saline water and many other pressures, every day is a challenge”. There have been several studies and documentation on the threats faced by the 102 islands of the Indian Sundarbans, 54 of which are inhabited. For example, Mousuni is one of the 102 islands on the Indian side of Sundarbans facing an existential threat. With homes swept away time and again by raging water and cyclonic effects and agriculture devastated by saline water, several people have been forced to migrate from here and many permanently. As people, mostly youth, migrate seasonally or permanently towards seemingly better opportunities, there are lesser hands left in the household to contribute towards livelihoods.

This, coupled with loss of livestock and land, temporarily or permanently, creates a vicious cycle of poverty that leaves the elder population, women and children vulnerable. For most of these households and communities, fisheries (capture of aquatic organisms including fish) and / or aquaculture is/was the mainstay. With the visible negative impacts of climate change that includes too much (rains, floods) or too little (dry season) water availability at different times of the year, the very high range of salinity fluctuations leaves very little room for both aquaculture as well as agriculture. The livestock do not remain secure as loss of livestock drains out the little resources left with these households.

Sundarbans is the delta formed by the confluence of the Padma, Brahmaputra and Meghna Rivers in the Bay of Bengal. It is the single largest mangrove forest in the world between India and Bangladesh with India owning 40% of it. The name “Sundarbans” is thought to be derived from Sundari (Heritiera fomes), the name of the large mangrove trees that are plentiful in the area. The forestland transitions into a low-lying mangrove swamp approaching the coast, which itself consists of sand dunes and mud flats and barren land and is intersected by multiple tidal streams and channels. Four protected areas in the Sundarbans are enlisted as UNESCO World Heritage Sites, viz. Sundarbans West (Bangladesh), Sundarbans South (Bangladesh), Sundarbans East (Bangladesh) and Sundarbans National Park (India).

Despite several protection acts, the Indian Sundarbans were considered endangered in a 2020 assessment under the IUCN Red List of Ecosystems framework. This makes both the ecosystem as well as the communities extremely vulnerable and susceptible to the calamities of nature. There is serious flooding and water logging in monsoon (which brings the salinity to its lowest) and extreme shortage of water during summers that shoots up the salinity to extreme highs (see vlog). The wide range, therefore, of the salinity, poses a serious threat to both the flora and fauna and makes livelihoods very difficult to manage both at household as well as ecosystem levels.

Having talked about the generic scenario above, the paper highlights examples from the Indian Sundarbans by way of observations from several visits and in-depth interactions with Government and Non-government agencies as well as community members in these islands. A lot is being said and only some being done in terms of long-term strategies as opposed to a lot being done on crisis management that turns out to be a band aid approach. What seems to be missing is the proactive approach and strategies. It is evident that while the crisis management strategy is clearly reactive in nature, little is being done as proactive and long-term approach. Even if some is done, organizations, collectives and even individuals tend to act in silos and largely miss out on the benefits of synergies between and amongst them.

During a visit immediately after one of the cyclones, it was observed that there were hundreds of families that had to move to higher grounds – the only higher grounds available being the primary and secondary roads. As a result of this, almost for three months, movements were completely stalled and availability of day to day needs including food and medical support was a huge challenge. Some families reported having lived in such conditions for three long months. All agriculture plots were submerged and farmers faced huge losses that included livelihoods, health and well-being in particular. And this happens regularly in the region…

Seasonal migration from the region is disturbingly high at 74% (Mistri, 2013). We came across stories of both parents migrating to earn a living, sometimes for extended periods of time, leaving behind very young children to the mercy of neighbours. So while the social capital is important and pays back, it certainly can never make up for parents’ absence. That is one of the major reasons many organizations working in the region would want to arrest or minimise seasonal migration by providing sufficiently good livelihood options and opportunities. While some agencies and researchers term it as “environmental migration”, the reasons could be well beyond environment alone though it plays an important part.

The crisis is coming, and we have to start working on what can be done in terms of mitigation and adaptation. One adaptation strategy could be Amphibious Living – essentially living on water rather than on land. While some work has been done on amphibious housing in Vietnam and Bangladesh (see link below) not much has been done on Amphibious Living as a whole[1].

Amphibious Living Opportunities – The ALO for Sundarbans

What has been stated above is just the tip of the iceberg. After several visits and consultations with local community members, including women and children as well as some NGOs and government agencies, it is evident that these communities will need to quickly adapt to “Amphibious Living”. The title “Amphibious Living Opportunities” abbreviated as ALO (আলো) in the local language, Bengali, means “illumination” or “light” and also signifies “dawn”.

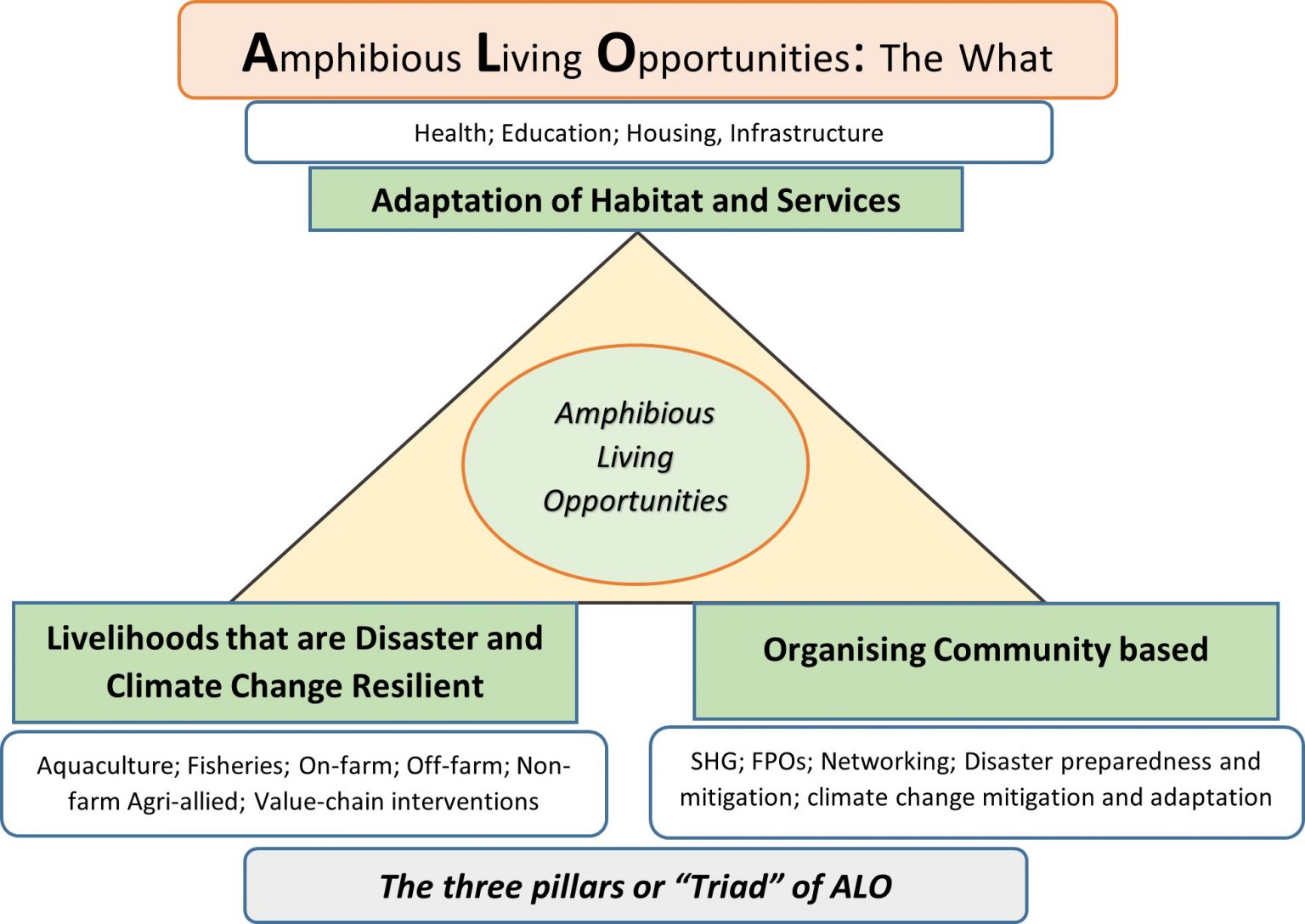

Amphibious living is a means through which communities need to adapt to extreme conditions of climate change. Promoting disaster and climate change resilient livelihoods in alignment with amphibious living will not only help the local communities to shape their livelihoods in accordance with climate change, but also reduce their vulnerability to climate risks and improve their living conditions. Disaster and climate change resilient livelihoods would involve promoting livelihoods in fisheries, agriculture and agri-allied activities.

Strengthening amphibious communities would involve strengthening communities to undertake initiatives for (a) ecological conservation; (b) disaster and climate change preparedness; (c) seeking improvements in infrastructure and services and (d) securing livelihood for all.

Amphibious living would involve redesigning the use of physical assets – The What – such as structures to prevent flooding, housing, building and also natural assets such as land and forest etc., which support amphibious living. It is being suggested that the this would involve a three pronged strategy: (A) Focus on basics of living – food, health, education and housing; (B) promoting amphibious livelihoods – through land and water based interventions that would include integrated farming approaches on one hand and involvement of women on the other; and (C) prioritize community based initiatives – building communities to adopt to amphibious living with a focus on SHGs, FPOs, networking, disaster preparedness and mitigation.

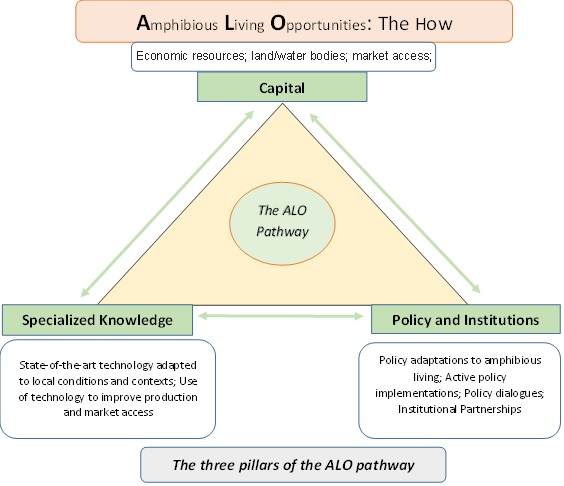

While this is easier said than done, pathways to enable this approach shall have to be put in place. The three strong pillars of this triad – The How – will consist of (A) Capital – economic resources, land/water bodies and access to markets; (B) Specialized knowledge and technology – state-of-the-art technologies adapted to local conditions and contexts, use of technology to improve production and market access; and (C) Policy and institutions – policy adaptations to amphibious living, active policy implementations, policy dialogues among and between stakeholders and institutional partnerships. Based on detailed discussions, some of the most appropriate interventions that can be thought of are being suggested below. The criteria used for suggesting these ideas is based on the following:

- Befitting local context – technically, socially, environmentally;

- Preferably ideas that the relevant organizations and / or the communities are familiar (and comfortable) with or are easy to adapt;

- Preference to high-value low-input crops;

- Appropriate interventions in the value chain;

- Consider natural calamities as limitations (not threats) and meticulously plan ‘around’ it, and

- Encourages partnerships with like-minded agencies.

It seems ironical that (fresh) water remains a major problem in the Sundarbans, a land that is often inundated by floods. Sundarbans is basically formed out of land surrounded by rivers and creeks. Yet both availability of potable water as well as freshwater for various purposes is seriously short of needs. To add to this, the rivers are saline to extremely saline in nature as is the groundwater in shallow aquifers. Salinity of water limits its use in domestic as well as for agricultural practices including aquaculture.

The deeper aquifers do have safe (fresh) groundwater but are few and far between, sometimes at depths of 300 meters below ground level. While the average rainfall in the region is impressively high at 1600 mm/annum, it lacks proper infrastructure and planning to maximize and hold this water or, for that matter, use it to recharge aquifers. Lack of upland freshwater discharge into these rivers allows the saline sea water to move deep inland. Salinity intrusion in the agricultural field makes agriculture extremely difficult. Electricity or the lack of it has been a major concern. So is health, education, infrastructure and better opportunities. The list of what is no more available or is lost temporarily or permanently is long.

Sugata Hazra, Head of the Department of Oceanography in Kolkata’s Jadavpur University, said: “We need to know why 63 out of around 1,000 villages in the Sundarbans are getting affected repeatedly. We need to find a solution for their safety.” He recommended putting up offshore wind breakers in some parts of western Sundarbans where the impact of cyclones is most pronounced.

Livelihoods that are Disaster and Climate Change Resilient

There are several livelihoods that exist and more can be taken up by the households. A combination of more than one of the following can either be started or scaled up:

Agriculture

- Salinity tolerant rice varieties: is something that can be tried in some areas with not extremely high salinity.

- Integrated Agri-aqua systems: will improve farm diversification which is a risk aversion strategy. See example in this video link.

Shubhankar Banerjee, Founder of NGO Soul which conducts medical camps in the villages on a regular basis, said, “Most of the people in the Sundarbans face stomach ailments majorly related to (in)digestion and acidity because of the saline water. Anaemia and calcium deficiency is another big health issue that they face – both females and males”.

Fisheries

- Short cycle fish species and ponds: should be considered to match the dry season with the culture of fish. This will allow the fish to reach marketable size before the rainy season sets in.

- Mud Eel Culture: Monopterus cuchia, also known as Kuche maach in WB, is found abundantly in freshwater marshy lands in several parts of India. While Monopterus eels may not necessarily fetch a high price (IndiaMart sells it for INR 350/Kg or US$ 4.30), it has a tremendous food value. These mud-eels can be reared in earthen ponds (see video link) to small containers (see video link) or in cemented tanks (see video link).

- Mud Crab Culture: Mud crab fattening predominates farming practices in Sundarban as opposed to grow-out culture. Locally, mud crab fattening is known as chamber chas and has been practiced since the late 1990s (Nandi et al., 2016). The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO of the UN) has a very simple and practical Crab Culture manual that can be downloaded from this link.

- Ornamental Fisheries: West Bengal in general and Kolkata in particular is the hub of ornamental fishes. Depending upon the species (both freshwater and brackish-water varieties), it is relatively far less complicated and also not a very expensive activity.

- Farmer owned and managed hatcheries: Other than the cost factor, access to good quality seeds and fingerlings is a major hurdle. Pilots of farmer(s) owned and managed hatcheries that will, in addition to providing sustainable source of seeds, fry and fingerlings in the region, also become a primary source of sustainable livelihood.

Bee Keeping and Livestock Rearing

- Bee keeping: The name Sundarbans comes from the famous Sundari tree and the scope of producing organic honey coming straight from the Sundarbans could be well placed. Our dependence on pollinators will probably grow over time as global diets diversify. This is already being done in the Sundarbans (see link).

- Backyard poultry farming: Several of the households, though, have backyard poultry, there numbers are meagre (sometimes as little as 5 to 10 birds per household). If this can be scaled up between 30 to 50 birds per HH, it can become an important livelihood activity catering to both food security as well as income generation. There are several examples of this being practiced in the Sundarbans (see link).

- Black Bengal goat: This variety, though mostly black, is also grey and white, is a prolific breeder and though may have very little milk value, is known for its meat and skin. In many parts of West Bengal and Bangladesh, this variety of goat means a lot to landless and poor households and communities. (See link).

Non-farm livelihoods

- Tourism as a composite livelihood sector: The Sundarban Tiger Reserve is a major tourism destination and a small number of local people participate in the tourism sector as vendors, boatmen and guides. As of now tourism is restricted to winter months that are pleasant and also have easier access to the islands given there are less chances or rain and floods.

How to make these livelihoods sustainable?

In addition to making them disaster and climate change resilient, there are at least three requirements for making these livelihoods sustainable:

Taking an Enterprise Approach: People have to move from subsistence to surplus production for the local and distant markets.

Starting with Own Capital: The second aspect is to mobilise capital for these new livelihood enterprises. Institutional credit is a predominant source of finance and plays a pivotal role in the development of an economy. But as the enterprises grow and some at the higher scale have to be set up, the investment per enterprise may be up to INR 1,000,000 ($12,260) per household and this will require bank financing.

Partnerships with Market Actors: Given the limitations of financial resources and / or lack of access for both individuals as well as communities, getting into sustainable partnerships create avenues. An example from the Sundarbans is that of “Kejriwal Honey”, one of the largest exporters of honey from India, that have partnered with local communities and have provided opportunities to households by providing training, infrastructure (bee boxes, etc.) and facilitation.

Organising Community-based Initiatives

Actions by individuals or a few households is not adequate to move the needle. What is needed are organised community based initiatives. We give below three examples:

Panchayats – Gram Panchayat and Panchayat Samitis

The primary unit of local self-government under the 73rd Amendment of the Indian Constitution is the Gram Panchayat, which is quite empowered in West Bengal. It has devolution of powers, funds and functionaries. Each Gram Panchayat has an appointed Secretary and at the Panchayat Samiti (Block) level there are a number of officials for different functions.

Cooperatives

The government has established several Large-Sized Multipurpose Co-Operative Societies (LAMPS) in the area and these need to be oriented towards amphibious living opportunities.

Women’s Self-Help Groups and SHG Federations

The concept of Self-Help Groups was primarily brought in as a tool to empower women and has helped the economic condition, decision-making power relating to expenditure, status within the family and the society has increased favourably for the women members.[1]

Fish Farmers’ Producer Organization (FFPO)

FPOs are becoming very popular and successful in several parts of the country with huge plans of thousands of more FPOs in the country. However, there are very few examples of FPOs in Fisheries – FFPOs. This needs to be the focus.

Amphibious Living Opportunities: How to Actualize These?

Capital

Among other support systems, adequate support of capital – economic resources, land/water bodies and eventually access to appropriate markets is important.

Specialised Knowledge

Each Amphibious Livelihood needs expert knowledge, its extension, and skills to implement the knowledge. To enhance productivity and market access, even the resource poor communities now have some degree of access to smart phones, for example.

Policy and Institutions

No single actor is capable of addressing the development problem alone. The Panchmukhi Samvaay or Collaborative Pentagon provides a practical structure for the implementation of inclusive and sustainable development. Its five sides are (1) Civil Society Institutions; (2) Government including elected Panchayats and Municipalities (3) Private Enterprise Sector – from micro to corporate (4) Financial Institutions and (5) Knowledge Institutions including Universities and the Media. The community is at the centre of all this. This is depicted below:

A Call to Action

As the darkness of human and economic losses caused by cyclones and climate change induced rise of sea level surrounds the Sundarbans, the communities need to be helped to usher in the new dawn of ALO – Amphibious Living Opportunities, comprising (i) adaptation of habitat and services (ii) livelihoods that are disaster and climate change resilient and (ii) organising community based initiatives. This is a call to action at various levels – individual households, small collectives, larger collectives and community in general; to adapt the habitat as well the livelihoods to the upcoming change. They will have to get together and prioritise activities in terms of urgency, ease, returns and importance – things that can and should be done immediately, those that are mid-term and eventually the long-term ecosystem improvement approach. They will have to work towards achieving institutional synergy – along the lines of the Panchmukhi Samvaay or Collaborative Pentagon suggested above. And all this will have to done urgently, they have only a few years to respond.

About the authors:

*Vijay Mahajan is the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of the Rajiv Gandhi Foundation and the Director of the Rajiv Gandhi Institute of Contemporary Studies. Vijay is the founder of the BASIX Social Enterprise Group which is engaged in livelihood promotion and supported the livelihoods of over three million low income households in over 20 states in India and six developing countries. Vijay founded PRADAN, a well-known Indian non-government organization (NGO), in 1982, and worked at PRADAN till the end of 1990. He established VikaSoko Development Exchange in 1991 jointly with his Woodrow Wilson School/Princeton classmates, Thomas Fisher, a British citizen and Geoffey Onegi-Obel, a Ugandan citizen, worked on social enterprises in India and East Africa. They ran VikaSoko till 1996, when Vijay established the first three entities of what later became the BASIX Social Enterprise Group.

**SS Tabrez Nasar, PhD, is former Dean, Institute for Livelihoods Research and Training (ILRT). He has a Ph.D in Life Sciences and having spent his initial years in teaching, he moved on to an international NGO, the International Institute of Rural Reconstruction (IIRR) with headquarters in the Philippines. After serving IIRR for over a decade, he joined an Inter-Governmental Organization – the Bay of Bengal Programme Inter-Governmental Organisation (BOBP-IGO). He then moved on as an Advisor to the Ministry of Planning and Finance, Government of Timor Leste. Tabrez came back to India and extended support to development organizations as a consultant before moving on to Basix Social Enterprise Group. He has been engaged with programs in India, the Philippines, Lao PDR, Cambodia, Viet Nam, Sri Lanka, Maldives, Bangladesh, Thailand, Tanzania, Ethiopia and Mozambique other than being exposed to several short-term activities (including consultancies) in over a dozen countries across the globe.

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank the team at the NGO Rajarhat PRASARI (http://www.prasari.org/ ), led by Saikat Pal, for many of ideas in this paper, garnered during several field visits by the authors. The authors are also thankful to many community members in the Sundarban Islands who provided very useful insights.

Reference: For the original paper, please visit https://www.rgics.org/wp-content/uploads/Policy-Watch-11.10_ENRS.pdf (see Paper #1.).

[1] (Source: www.igi-global.com – Handbook of Research on Microfinancial Impacts on Women Empowerment, Poverty, and Inequality; 2019).

[1] https://floodresilience.net/resources/item/beat-the-flood-flood-resilient-homes-in-bangladesh/

This entry was posted in: Aquaculture, Asia, Concepts, Theory, Country, Fisheries, India, Men, Women